Application of Mucuna pruriens pellets, organominerals and Trichoderma harzianum agents in coffee seed beds (Coffea arabica)

Aplicación de pellets de Mucuna pruriens, organominerales y agentes de Trichoderma harzianum en lechos de semillas de café (Coffea arabica)

Omar Porras Chacón1; Jimmy Porras Barrantes2; Roberto Naranjo Zuñiga3;

Andres Zuñiga Orozco3 *

1 Faculty of Agronomy, State at Distance Education University (UNED), 474-2050, San José, Costa Rica.

2 Research Department, Tarrazú Cooperative (CoopeTarrazu), 10501, San José, Costa Rica.

3 Faculty of Agronomy, State at Distance Education University (UNED), 474-2050, San José, Costa Rica / Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies Laboratory (EMA-Lab), Cartago, Costa Rica.

ORCID de los autores:

O. Porras: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-9031-7035 J. Porras: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-7565-7349

R. Naranjo: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-0601-2111 A. Zuñiga: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8214-4435

ABSTRACT

The excessive use of chemical fertilizers in agriculture has degraded soil quality, reduced fertility and caused environmental problems such as nutrient leaching. In response, regenerative practices are being explored to restore soil health and promote sustainable farming. This study evaluated the effects of nutrient-rich pellets made from Mucuna pruriens L., coffee husk-derived organominerals, monoammonium phosphate (MAP), and the biocontrol fungus Trichoderma harzianum Rifai on coffee seedlings (Coffea arabica). Conducted in a greenhouse in Tarrazu, Costa Rica, the experiment used eight treatments with twenty replicates each. The most effective formulation, 60% M. pruriens, 20% organominerals, and 20% MAP, applied at 100 – 150 g per plant, significantly improved seedling growth, nutrient uptake, microbial respiration, and plant survival. This mix also showed favorable chemical properties, including high nitrogen and phosphorus levels, near-neutral pH, and a low carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, enhancing nutrient availability. The addition of T. harzianum contributed to effective root disease control and was compatible with organic matter. Overall, the study highlights these pellets as a sustainable, multifunctional solution for plant nutrition and disease management in coffee nurseries, with potential applications in other crops. Further research is needed to evaluate their economic viability and potential for commercial use.

Keywords: pellets; Mucuna pruriens; organominerals; nutrients; microbial biomass.

RESUMEN

El uso excesivo de fertilizantes químicos en la agricultura ha degradado la calidad del suelo, reducido la fertilidad y ha causado problemas ambientales, como la lixiviación de nutrientes. En respuesta, se están explorando prácticas regenerativas para restaurar la salud del suelo y promover la agricultura sostenible. Este estudio evaluó los efectos de pellets ricos en nutrientes hechos de Mucuna pruriens L., organominerales derivados de la cáscara de café, fosfato monoamónico (MAP) y el hongo de biocontrol Trichoderma harzianum Rifai en plántulas de café (Coffea arabica). Realizado en un invernadero en Tarrazú, Costa Rica, el experimento utilizó ocho tratamientos con veinte réplicas cada uno. La formulación más efectiva (60% M. pruriens, 20% organominerales y 20% MAP), aplicada a 100 - 150 g por planta, mejoró significativamente el crecimiento de las plántulas, la absorción de nutrientes, la respiración microbiana y la supervivencia de la planta. Esta mezcla también mostró propiedades químicas favorables, incluyendo altos niveles de nitrógeno y fósforo, un pH casi neutro y una baja relación carbono-nitrógeno, lo que mejoró la disponibilidad de nutrientes. La adición de T. harzianum contribuyó a un control eficaz de enfermedades radiculares y fue compatible con la materia orgánica. En general, el estudio destaca estos pellets como una solución sostenible y multifuncional para la nutrición vegetal y el manejo de enfermedades en viveros de café, con posibles aplicaciones en otros cultivos. Se requiere mayor investigación para evaluar su viabilidad económica y su potencial para uso comercial.

Keywords: pellets; Mucuna pruriens; organominerals; nutrients; biomasa microbiana.

1. Introduction

In agricultural production, side effects occur when using chemical fertilizers. Some of these effects involve the wear and tear of the physical-chemical properties of the soil and thus affect its degree of fertility. In addition, the leaching of fertilizers into water sources has an environmental impact. Due to the above, regenerative management practices are recommended that restore nutrient levels, as well as the structure of the soil and conserve the environment.

This issue generates concern for producers worldwide, since it generates a decrease in production and degradation of the state of the soil (Arias et al., 2017). Classic agricultural models are unsustainable. The fight against desertification and drought, as well as the preservation of natural resources, leads us to seek new forms of sustainable agriculture.

According to the problems presented, the use of green manure from legumes is part of a technological strategy that has been investigated and tested by farmers, proving to be efficient and economically viable. Its objective is the increase and conservation of soil organic matter and nutrients, especially nitrogen (Garro, 2016; Rojas et al., 2020).

The structure of the soil is preserved by supplying organic matter from green manure. With the use of these living or dead covers, the soil is protected from the impact of rain, sunlight and desiccation. In addition, they can provide nitrogen through symbiotic fixation with bacteria.

One of the most investigated species is Mucuna pruriens L. DC (Fabaceae), a legume native to India and acclimated to tropical conditions (Brunner et al., 2011). Nitrogen incorporation is reported in the order of 80.9 to 331 kg·ha⁻¹·year⁻¹ (Brunner et al., 2011; Céspedes et al., 2019; Klassen et al., 2006; Ravi et al., 2018).

Agricultural production systems allow sowing and incorporating M. pruriens but there are cases, such as greenhouse production, low growing vegetables or organoponic systems, where it becomes impossible. On the other hand, planting this plant in the middle of crops produces an ideal microclimate as a hiding place for snakes and this entails risk for field workers. Finally, in low-growing vegetable crops it cannot be planted due to a competition effect.

It is for the above that, the development of a pelletized presentation seeks to solve all these application difficulties, promote its use, acceptance among farmers and improve the content of nutrients present in the dry matter of M. pruriens. This presentation has a series of advantages such as: dosage control, possibility of transport and storage, compatibility with biological controllers, they do not give off a bad odor, they improve the soil structure and provide an environment conducive to the development of the soil microbiome. In addition, atmospheric CO2 is captured through plant material and carbon is incorporated into the soil through the pellet, thereby contributing to mitigating climate change.

There are few documented studies where green manure pellets are used. However, some antecedents have been presented with the use of pelleted alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), red clover (Trifolium pratense L.) (Gatsios et al., 2021; Kaniszewski et al., 2019) and M. pruriens (Martinez-Alfaro & Zuñiga-Orozco, 2024). Other researchers experimented with bovine manure pellets (Liu et al., 2019). However, the combination of M. pruriens with organominerals and biocontrollers haven’t been explored.

Organo-minerals are another promising raw material for application in crop nutrition. It consists of the combination of organic matter and chemical fertilizers that are generally accepted by organic certifiers (calcium carbonate, magnesium sulfate, potassium sulfate, among others) (Martinez et al., 2024). Studies are recorded where they have been applied to various crops (Wen et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2023).

In this study, it was proposed to use green manure pellets with organominerals, which was called PAVOS (for its Spanish acronym: “Pellets de abonos verdes con organominerals”). In addition, MAP was added as a phosphate source necessary for the rooting period and T. harzianum as a biological controller of root diseases.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the raw materials mentioned to determine the growth of coffee seedlings and control of soil diseases. The above sought to stimulate the circular economy by taking advantage of agro-industrial waste, reducing the application of chemical fertilizers and contributing to the development of regenerative agriculture.

2. Methodology

2.1 Study site and plant material

The sowing of M. pruriens was carried out in the months of July to October in Perez Zeledón, San José, Costa Rica (Altitude 690 meters above sea level, 23 °C, 70% - 85% relative humidity, 2944 mm/year, 9°13'29.4"N - 83°38'03.3"W). The seed was acquired from local growers, soaked in water for 12 hours prior to sowing and sown at a depth of 3 - 5 cm, placing 2 seeds per point. A planting distance of 2 x 2 m was used, and irrigation was maintained for the 3 months of growth. Before flowering it was harvested to dry the fresh material.

The pelletizing process was carried out at Cartago campus of the State Distance University (UNED), Costa Rica (9°51'19.3"N - 83°55'05.1"W).

The application of the pellet was carried out in the greenhouse of the facilities of the Center for Organic Agriculture (CEDAO, spanish acronym) belonging to CoopeTarrazú coffee cooperative in Tarrazú, San José (1429 meters above sea level, 19 °C, 87% - 92% relative humidity, 1221 mm/ year, 9°39'23.6"N - 84°01'27.4"W). The growth and evaluation were carried out for a period of 6 months during the months of October to April 2023. The coffee variety used for this study was San Isidro 48 because it was of interest to the cooperative. The soil used in the 2.5 L bags was an andisol with loam to clay loam texture with pH 4.9.

2.2 Pelletizing process

Before pelleting, the fresh plant material needed to be dried, for this, it was placed in a greenhouse for 3 days at an average temperature of 32 °C. Once dry and brittle it was put through a corn grinding machine to refine the material. With the fine material, M. pruriens was mixed with coffee husk organominerals Ecofertil® (O.M) and monoammonium phosphate or MAP (12-60-0) according to each planned formulation (Table 1). A pelletizing machine (Teknomakinas®) designed for this purpose was used. The machine was adjusted so that the pellets were 1 cm high and diameter.

Each mixture was homogeneously mixed with water and oil until it reached 18% - 20% humidity. Once the pellet was obtained, it was left for 7 days drying and then packed in paper bags. Once the consistency of the material was hard, it was applied to the coffee seedlings.

A sample was taken from the three base formulations of the PAVOS (70% M. pruriens + 30% O.M, 65% M. pruriens + 25% O.M + 10% MAP and 60% M. pruriens + 20% O.M + 20% MAP) in order to send to laboratory for a complete chemical analysis, including carbon and electrical conductivity. The organic carbon content was determined using the dry combustion method with an elemental analyzer equipped with infrared detection, through high-temperature combustion (≈950 – 1200 °C) in the presence of oxygen. Electrical conductivity (EC) was determined using the soil–water extract method. The sample was air-dried and sieved (<2 mm), then mixed with distilled water at a 1:2 (w/v) ratio. The suspension was shaken for 30 minutes and allowed to settle. EC in the supernatant was measured with a conductivity meter previously calibrated with standard KCl solutions. Results were expressed in mS·cm⁻¹ at 25 °C.”

Table 1

Treatments and different formulations of PAVOS applied in coffee seedbed.

Treatment | Description | Mix (per each 1 kg) | Dose (g·pl-1) | Application frequency |

1 | 70% M. pruriens + 30% O.M* | 700 g M. pruriens 300 g O.M | 100 | 4 (each 25 g) |

2 | 65% M. pruriens + 25% O.M + 10% MAP | 650 g M. pruriens 250 g O.M 100 g MAP | 100 | 4 (each 25 g) |

3 | 60% M. pruriens + 20% O.M + 20% MAP | 600 g M. pruriens 200 g O.M 200 g MAP | 100 | 4 (each 25 g) |

4 | 70% M. pruriens + 30% O.M + | 700 g M. pruriens 300 g O.M | 150 | 4 (each 37.5 g) |

5 | 65% M. pruriens + 25% O.M + 10% MAP | 650 g M. pruriens 250 g O.M 100 g MAP | 150 | 4 (each 37.5 g) |

6 | 60% M. pruriens + 20% O.M + 20% MAP | 600 g M. pruriens 200 g O.M 200 g MAP | 150 | 4 (each 37.5 g) |

7 | Commercial Control (T.C) | Chemical Fertilizer (6-24-12) | 150 | 4 (each 37.5 g) |

8 | Absolute Control (T.A) | --- | --- | ---- |

* O.M: Organominerals.

2.3 Biometric and chemical analysis

At 6 months of age, the biometric variables were evaluated: height (cm), root length (cm), stem thickness (cm), fresh weight of stem and root (g), and finally, dry weight of stem and root (g). At that same time, chemical soil analyzes were taken to determine the contents and chemical properties for each treatment and sent to the laboratory of the Agronomic Research Center (CIA-UCR), the KCl-Olsen method was used. Soil samples were taken from each treatment at surface layer of 0 - 20 cm. At the beginning of the experiment, a composite sample of the soil used was taken and used as a comparison point.

To record the fresh plant weight in grams, the seedlings were weighed by washing the roots and leaving only the plant material and then weighed on a precision analytical balance. To record the dry weight in grams of both the aerial and root parts, the plants were dried in an oven at 70 °C until reaching a constant weight.

As to foliar analyses, they were also taken at 6 months, choosing the 4 developed leaves closest to the growth point of the plants. In each treatment, 500 g was taken to send to the laboratory and analyze by the chemical digestion method.

Soil and foliar levels were analyzed using reference tables for coffee crops according to Melendez & Molina (2002) and Méndez & Bertsch (2012).

2.4 Application of T. harzianum

Once the pellets were dry processed, T. harzianum was applied at a concentration of 1x108 CFU/g in powder in a dose of 5 g·kg-1 pellet. The pellet was homogenized by manual agitation within the packaging. At 6 months of age, the survival count was recorded.

2.5 Soil microbial respiration

Each plant was measured for microbial respiration by ppm of CO2 taking a sample of soil from the first 10 cm of depth of each one. A portable infrared gas analyzer (IRGA) camera with a range between 0 - 10000 ppm (IRGA, LI-COR® Biosciences) was used. The CO2 concentration was quantified every 4 seconds for a period of 24 hours at an average temperature of 20 °C. It was done in the dark to prevent light from interfering with the measu-rement.

2.6 Treatments and experimental design

The treatments proposed are detailed in Table 1. A total of 160 plants were used, taking 20 repetitions for the eight planned treatments. The formulation was designed to integrate raw materials tailored to the requirements of the early phenological stage of plant growth

A completely randomized design (CRD) was used, with eight treatments and 20 replicates per treatment, totaling 160 experimental units.

2.7 Statistical analysis

To observe the distribution of the data, a Shapiro-Wilks normality test and a Kolgomorov goodness-of-fit test were performed to describe the distribution of the data. After this, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare the variances between the means of the treatments. To separate the means, when significant differences were observed between treatments, the Tukey mean separation test was used with a significance level of p ≤ 0.05 (95% reliability).

To transform the survival percentage data, the arcsine of the square root of the percentage was used, prior to carrying out the ANOVA. For the all the statistical analysis, Rstudio® version 4.4.3 and Infostat® version 2020 were used.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Nutrient contents in pellets

The chemical analyzes of the three PAVOS formulations designed in this study are presented below (Table 2). The results were as expected, in terms of proportions according to the elements used. The formulation 60% M. pruriens + 20% O.M + 20% MAP stands out, since it has the highest content of N and P, as well as having the highest EC, pH close to neutrality and the lowest C/N ratio. Also, worth noting is the high carbon content in the three formulations used.

The design of the pellets contemplated some critical elements that are important for initial growth, that’s why phosphorus and nitrogen were added by MAP. Nutrient accumulation has an effect on plant growth and as well low C/N ratio keeps nutrients available in the soil. Low C/N ratio in raw materials from legumes is favorable because it facilitates its rapid degradation due to intense microbial activity (Matos et al., 2011; Cardoso et al., 2018), researchers recommend a range between 15 - 30 (Martinez et al., 2024). This occurred in this study where the C/N ratio of the raw materials was between 14.3 - 25.2. According to the above, the designed PAVOS complied with what was indicated in the literature.

Table 2

Chemical properties of the three main formulations of the PAVOS used in the study

Formulation | N | P | K | Ca | Mg | S | | Fe | Cu | Zn | Mn | B | pH | EC mS·cm-1 | C % | C/N |

% | | mg·kg-1 |

70% M. pruriens + 30% O.M* | 1.88 | 0.54 | 1.82 | 2.22 | 1.28 | 0.16 | | 8670 | 26 | 113 | 250 | 16 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 47.3 | 25.2 |

65% M. pruriens + 25% O.M + 10% MAP | 2.48 | 2.58 | 1.78 | 2.04 | 1.22 | 0.16 | | 7026 | 24 | 106 | 228 | 18 | 6.5 | 12.4 | 44.9 | 18.1 |

60% M. pruriens + 20% O.M + 20% MAP | 3.04 | 4.81 | 1.56 | 1.76 | 0.98 | 0.15 | | 5876 | 21 | 97 | 195 | 16 | 6.2 | 24.7 | 43.3 | 14.3 |

*O.M: Organominerals.

3.2 Biometric measures and growth

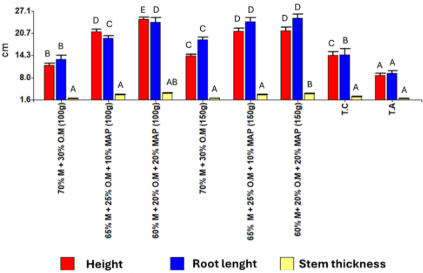

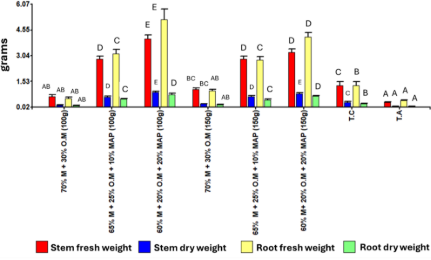

Figures 1 and 2 show the values of the biometric variables. In general, greater height, stem length, basal stem thickness, stem and root dry weight were obtained in plants applied with the formula-tion of 60% M. pruriens + 20% Organo-minerals + 20% MAP, both at 100 g/plant and at 150 g/plant, the above in relation to the commercial (T.C) and absolute control (T.A) (p < 0.05).

Figure 1. Growth of coffee seedlings in terms of root length, stem length and stem thickness evaluated at 6 months of age. Different letters indicate significant differences based on a comparison of means with ANOVA test (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 2. Growth of coffee seedlings in terms of fresh weight and dry weight of stem and root evaluated at 6 months of age. Different letters indicate significant differences based on a comparison of means with ANOVA test (p ≤ 0.05).

The biometric variables chosen were of special importance to understand the effect of PAVOS on plant growth. The treatments demonstrated effectiveness in relation to the absolute and commercial control for most of the variables, especially in the formulation 60% M. pruriens + 20% O.M + 20% MAP. It is possible that applying mixed raw materials is better than applying them individually considering the diverse literature reports with different raw materials.

While it is true, there is no evidence of the use of M. pruriens pellets with organominerals and T. harzianum, some studies have pelleted raw materials. In relation to the above, there is reported improvement in the growth and yield of corn using organo-minerals but not in pelleted form (Hammed et al., 2019). Researchers explored pelletizing alfalfa to apply to tomatoes, as a result there was an increase in N at foliar level, as well as an increase in yield in relation to control (Gatsios et al., 2021). Alfalfa and red clover pellets were applied in open field in onion cultivation, an increase in growth and yield was also recorded (Kaniszewski et al., 2019).

To meet the needs of coffee cultivation, the combination of different nutrient sources is required, and nitrogen from legumes provides a sustainable and viable alternative (Martinez et al., 2024). However, in this study, coffee husk improved with minerals (organominerals) was added to the legume species and, in turn, reinforced with a biological controller (T. harzianum). The above led to the term PAVOS, and, according to the results obtained, it is seen as an integrated alternative for plant nutrition and biocontrol of diseases at the coffee seedling level, it could even be adapted to other growth stages in other crops.

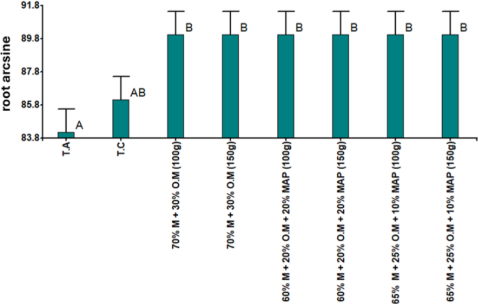

3.3 Plant survival

The following figure shows the survival of coffee plants in treatments applied with T. harzianum mixed with the PAVOS (Figure 3). All treatments recorded a greater number of live plants in relation to the commercial and absolute controls (p < 0.05).

The advantage of making PAVOS compatible with biological controllers such as T. harzianum was one of the facts observed in this study and this is important because this fungus requires organic matter to survive (Organo et al., 2022). The biocontrol observed collaborate to a better management in organic production but even it could be used in regenerative agriculture. In previous studies, it has been possible to identify viable spores and in sufficient quantity, for up to 6 months of storage, after having been applied to PAVOS (unpublished data). The above is important in terms of the product being taken to a commercial stage.

3.4 Soil microbial respiration

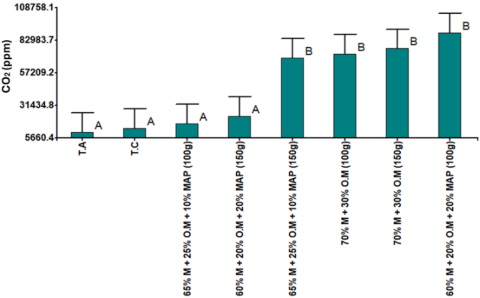

In Figure 4, it was determined that four treatments applied with PAVOS (including the formulation with 60% M. pruriens + 20% Organominerals + 20% MAP) had greater microbial activity, in relation to the commercial, absolute control and two treatments (p < 0.05).

Figure 3. Survival of coffee seedlings applied with PAVOS enriched with T. harzianum and evaluated at 6 months of age. Different letters indicate significant differences based on a comparison of means with ANOVA test (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 4. Measured microbial respiration obtained in the treatments applied with PAVOS in coffee seedlings and evaluated at 6 months of age. Different letters indicate significant differences based on a comparison of means with ANOVA test (p ≤ 0.05).

In relation to microbial activity, it should be noted that the soil microbiota plays an important role in the dynamics of nutrients available to roots (Paolini, 2018; Pardo-Plaza et al., 2019; Carvalho et al., 2024) and it has even been discovered that, in coffee, it influences the quality of the cup (Rojas-Chacón et al., 2024). Studies have been reported where the application of green manure fertilizers in conjunction with organo-minerals can change the composition of the microbiota (Wen et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2023). In relation to the above arguments, the use of pellets with green manure and coffee husk leads to an increase in the amount of carbon, and this could favor bacterial diversity in the soil profile.

3.5 Soil nutrient content

The following tables show the soil variables (Table 3) and nutrient content (Table 4) in the soil applied with PAVOS, as well as the same variables present in the initial soil (without application). The respective controls are also presented.

In Table 3 we observed that the acidity and % S.A increased in treatments where the formulation had MAP, this in relation to the initial soil, however, the commercial control increases its value to a greater magnitude. The above is an indication of soil acidification, however, with the PAVOS, the level obtained by the commercial control was not reached. The same was observed for EC.

Carbon was increased when was applied with PAVOS being higher with the formulation with M. pruriens + 20% Organominerals + 20% MAP (150 g/plant)

In Table 4 there was a clear increase in P content in all treatments but to a greater extent where MAP was added in PAVOS. Also, in these mentioned treatments Mg, K, Zn, Fe y Mn increased (p < 0.05). Ca y Cu were reduced since initial content.

Table 3

Soil analysis of all treatments applied with PAVOS in relation to the initial soil and the controls. Different letters indicate significant differences based on a comparison of means with ANOVA test (p ≤ 0.05)

Treatment | pH (5.5-6.5) | Acidity (<1) cmol(+)·L-1 | CICE (10-20) % | A.S (<20) % | EC (<2) mS·cm-1 | C (2-5) % | N (0,1-0,2) % | C/N (12-25) |

Initial soil | 4.9 | 0.42 | 14.3 | 3 | 1.2 | 5.3 | 0.3 | 15.6 |

70% Muc. + 30% O.M* (100 g/pl) | 6.8 f | 0.1 a | 16.1 a | 0.7 a | 0.4 a | 5.7 ab | 0.4 ab | 13.1 a |

65% Muc. + 25% O.M + 10% MAP (100 g/pl) | 5.3 c | 5.1 bc | 15.2 a | 3.0 ab | 1.6 bcd | 6.1 b | 0.5 abc | 12.5 a |

60% Muc. + 20% O.M + 20% MAP (100 g/pl) | 5.2 bc | 0.6 c | 12.7 a | 4.7 bc | 0.9 abc | 5.2 a | 0.4 ab | 11.2 a |

70% Muc. + 30% O.M (150 g/pl) | 6.3 e | 0.1 a | 16.6 a | 0.7 a | 0.4 ab | 6.3 bc | 0.5 bc | 12.3 a |

65% Muc. + 25% O.M + 10% MAP (150 g/pl) | 5.1 b | 0.5 bc | 12.5 a | 4.3 bc | 1.1 abc | 5.8 ab | 0.5 bc | 11.2 a |

60% Muc. + 20% O.M + 20% MAP (150 g/pl) | 5.0 b | 1.0 d | 13.6 a | 7.0 c | 2.0 cd | 6.8 c | 0.6 c | 11.4 a |

T.C | 4.3 a | 1.4 e | 12.7 a | 12.0 d | 2.5 d | 6.0 b | 0.4 a | 15.4 a |

T.A | 5.7 d | 0.3 ab | 13.1 a | 2.0 ab | 0.1 a | 4.8 a | 0.4 a | 12.6 a |

*Muc= M. pruriens O.M= Organominerals T.C= Commercial Control T.A= Absolute Control.

Table 4

Nutrient content in the soil applied with the PAVOS in relation to the initial soil and controls. Different letters indicate significant differences based on a comparison of means with ANOVA test (p ≤ 0.05)

Treatment | Ca | Mg | K | | P | Zn | Cu | Fe | Mn |

(5-10) | (1-3) | (0.2-0.5) | | (20-60) | (1-5) | (0.2-2) | (20-100) | (10-50) |

cmol(+)·L-1 | | mg·L-1 |

Initial soil | 10.6 | 2.1 | 1.2 | | 33 | 2 | 3 | 95 | 46 |

70% Muc. + 30% O.M (100 g/pl) | 9.7 b | 4.2 bc | 2.1 bc | | 32 a | 3.1 a | 3 b | 102 a | 31.3 a |

65% Muc. + 25% O.M + 10% MAP (100 g/pl) | 8.0 ab | 4.7 bc | 1.9 bc | | 578 c | 4.8 a | 2.0 a | 143 b | 131 bc |

60% Muc. + 20% O.M + 20% MAP (100 g/pl) | 6.9 ab | 3.7 b | 1.5 b | | 605 c | 4.3 a | 2.0 a | 166 bc | 135.7 b |

70% Muc. + 30% O.M (150 g/pl) | 8.1 ab | 5.4 c | 2.9 d | | 71 a | 6.0 a | 2.3 ab | 87 a | 25.7 a |

65% Muc. + 25% O.M + 10% MAP (150 g/pl) | 5.9 a | 4.1 bc | 2.0 bc | | 670 c | 6.4 a | 2.0 a | 145 b | 143.3 b |

60% Muc. + 20% O.M + 20% MAP (150 g/pl) | 6.5 ab | 4.1 bc | 2.1 c | | 892 d | 6.4 a | 2.0 a | 139 b | 164.7 bc |

T.C | 7.9 ab | 1.2 a | 2.1 c | | 212 b | 6.2 a | 2.3 ab | 196 c | 206.3 c |

T.A | 9.7 b | 2.2 a | 0.8 a | | 6.0 a | 4,0 a | 3 b | 140 b | 35 a |

* Muc= M. pruriens O.M= Organominerals T.C= Commercial Control T.A= Absolute Control.

According to soil nutrient content. The treatments containing MAP showed an increase in acidity and % S.A compared to the initial soil; however, the commercial control exhibited a higher significant increase. This suggests soil acidification, although the PAVOS did not reach the levels observed in the commercial control. This was also observed in a previous study using M. pruriens pellets (Martinez-Alfaro & Zuñiga-Orozco, 2024). Acidification is common in agricultural systems where chemical fertilizers are applied but the application of organic matter increases cation exchange capacity and microbial activity, factors that contribute to reducing exchangeable aluminum and phosphorus adsorption to soil colloids (Doran & Parkin, 1996).

The carbon contained in the PAVOS was incorporated into the soil and increased its value, compared to the initial soil and absolute control. Regarding carbon and nitrogen, a better content was observed in the soil in the treatment 60% M. pruriens + 20% O.M + 20% MAP (150 g/plant). Researchers reported carbon incorporation when applying organo-minerals in the range of 4.4 - 12%, which coincides with this study where 5.2 -6.8% was recorded (Xu et al., 2023).

It is important to mention that carbon incorporation is a climate change mitigation measure by using M. pruriens as a “bridge” species between atmospheric carbon and the carbon that is incorporated into the soil after application. In this regard, is important to mention that, in conservationist organic coffee production systems, organic matter in the soil increases and this makes possible the sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere (Niguse et al., 2022).

One aspect to consider in the application of this pellets is electrical conductivity (EC). An increase was observed in the pellet formulation as a greater amount of MAP was added, however, when applied to the plants the value was much lower. An adequate EC range for most crops is 1.2 - 2,0 mS/cm (Havlin et al., 2013), this coincides with what was recorded in this study (0.4 – 2.5 mS /cm). Despite the above, the most promising formulation recorded in this experiment (60% M. pruriens + 20% O.M + 20% MAP) presented the highest EC value (2.0 mS/cm), therefore, it is not recommended to increase the amount of MAP in said formulation. This factor is critical because damage to roots could occur, and this has implications for the potential success of the input at a commercial level.

3.6 Foliar nutrient content

Below are the foliar levels obtained when applying PAVOS in relation to commercial control (Table 5). The absolute control could not be analyzed due to the small amount of leaf tissue and this correlates with its poor growth, in turn, reinforces the hypothesis that the fertilization practice is necessary to accumulate dry matter and improve growth.

In general, the application of PAVOS equals or exceeds chemical fertilizer depending on each element. It should be noted that the treatment 60% M. pruriens + 20% O.M + 20% MAP at 150 g/plant presented the highest levels of N, P, Ca, Mg and Mn. Additionally, Zn was among the highest values. Calcium, Magnesium and Sulfur at foliar level were reduced in the treatments applied with 70% M. pruriens + 30% O.M in 100 and 150 g/plant in relation to the commercial control. However, this same formulation presented the highest levels of K.

Table 5

Nutrient content at foliar level in treatments applied with the PAVOS in relation to controls. Different letters indicate significant differences based on a comparison of means with ANOVA test (p ≤ 0.05)

Treatment | N | P | Ca | Mg | K | S | Fe | Cu | Zn | Mn | B |

Optimal levels | 2.3-2.8 | 0.12-0.2 | 1.1-1.7 | 0.2-0.35 | 1.7-2.7 | 0.2-0.3 | 75-275 | 6-12 | 15-30 | 50-150 | 60-100 |

70% Muc. + 30% O.M (100g/pl) | 3.8 a | 0.2 ab | 0.7 a | 0.18 a | 3.4 c | 0.18 a | 159 a | 11 b | 15.0 ab | 84 ab | 24 c |

65% Muc. + 25% O.M + 10% MAP (100g/pl) | 5.1 a | 0.25 bc | 1.3 cd | 0.27 c | 2.2 a | 0.23 b | 145 a | 2 a | 15.0 ab | 504 b | 19 ab |

60% Muc. + 20% O.M + 20% MAP (100g/pl) | 5.2 bc | 0.33 d | 1.1 b | 0.29 cd | 2.2 a | 0.23 b | 142 a | 2 a | 14.7 ab | 648 c | 20 ab |

70% Muc. + 30% O.M (150g/pl) | 3.7 a | 0.18 a | 0.6 a | 0.16 a | 3 b | 0.17 a | 147 a | 9 b | 12.3 a | 84 ab | 23 bc |

65% Muc. + 25% OM + 10% MAP (150g/pl) | 5.1 b | 0.28 cd | 1.2 bc | 0.27 c | 2.2 a | 0.22 b | 137 a | 2 a | 15.7 b | 519 b | 20 ab |

60% Muc. + 20% O.M + 20% MAP (150g/pl) | 5.8 e | 0.38 e | 1.3 d | 0.31 d | 1.9 a | 0.23 b | 96 a | 1 a | 15.3 ab | 774 d | 16 a |

T.C | 5.6 cd | 0.17 a | 0.7 a | 0.23 b | 1.9 a | 0.22 b | 103 a | 3 a | 12.7 ab | 554 b | 22 bc |

T.A | *Not enough leaf tissue to perform laboratory analysis |

* Muc= M. pruriens O.M= Organominerals T.C= Commercial Control T.A= Absolute Control.

Another aspect to consider when applying PAVOS is that the addition of P in high quantities normally causes indisposition of elements such as Ca, Mg, Fe, Mn, Cu and Zn. In this study, when PAVOS were applied, it was observed that Cu and Zn were in low quantities at foliar level in relation to the recommended levels. The above is a criterion to consider in terms of nutritional management of coffee seedlings, but it could be an aspect that is repeated in other crops.

Finally, we observed that pellet is greatly influenced by soil moisture and irrigation, this is critical for proper pellet dissolution. In our opinion watering should be done immediately after pellet application for a better use.

4. Conclusions

Summarizing what was observed, the growth of plant tissue was due to a relationship between growth, formulation used, proportion of nutrients applied, plant survival and possibly microbial activity. Regardless of the formulation, it was possible to accumulate macro and micronutrients, both at foliar level and in the soil, especially N, P, K, Mn and Zn. The most promising formulation (60% M. pruriens + 20% O.M + 20% MAP) also presented the characteristic of being the one that accumulated the greatest amount of N and P in both soil and plants and this was expected due to the addition of MAP. Additionally, this treatment managed to accumulate the highest amount of C in soil and its C/N ratio was one of the lowest.

Among the advantages of this bioinput studied, it can be mentioned that it allows several agricultural practices to be carried out at a single moment. The above is because this pellet has macro and micronutrients, improves plant growth, is compatible with T. harzianum as a biological controller and has a high carbon content, which improves the physicochemical conditions of the soil. It may also be compatible with growth-promoting bacteria but needs more research.

In terms of cost reduction, this technology has very promising potential, since it could reduce the cost of hand labor, and this is important especially in countries where this item is high. It must be considered that PAVOS incorporate T. harzianum to replace fungicides, incorporate nutrients to the crop to replace chemical fertilizers and add carbon to the soil to replace an organic amendment, which leads to reducing three agricultural practices in one time of application.

Other crops, application rates, and formulations tailored to specific phenological stages are also important topics that should be explored in order to adapt this input to different conditions. A line of research yet to be explored is to determine production costs, the market and a pre-feasibility study for potential commercialization.

Acknowledgements

We thank COOPETARRAZU cooperative, Laboratory Program (PROLAB) of the School of Exact and Natural Sciences (ECEN) of the State at Distance University (UNED), the Center for Change Management and Regional Development (CGCDR) of Cartago and the Laboratory of Strategies for Mitigation and Adaptation to Climate Change (EMA-Lab). All of the above for financing, loan of facilities, equipment maintenance and technical support.

Referencias bibliográficas

Arias, A., Brenes, P., Sánchez, L., & Peña, W. (2018). Mineralization of Mucuna pruriens and Crotalaria juncea in two soil orders in Costa Rica. Repertorio Científico, 20(2), 91-96. https://doi.org/10.22458/rc.v20i2.2391

Brunner, B., Beaver, J., & Flores, L. (2011). Informative Sheet. Mucuna pruriens. Department of Crops and Agro-Environmental Sciences, Lajas Agricultural Experiment Station, Puerto Rico. Yumpu, 1, 1-5.

Cardoso, R. G. S., Pedrosa, A. W., Rodrigues, M. C., Santos, R. H. S., Martinez, H. E. P., & Cecon, P. R. (2018). Intercropping period between species of green manures and organically-fertilized coffee plantation. Coffee Science, 13, 9-22. https://doi.org/10.25186/cs.v13i1.1332

Carvalho, F. F., Barreto-García, P. A. B., Pérez-Maluf, R., Marques, P. E., Rodriguez, F., Chaves, T., & Nunes, M. (2024). Effects of Coffea arabica cultivation systems on tropical soil microbial biomass and activity in the northeast region of Brazil. Agroforestry Systems, 98, 2397-2410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-024-01026-2

Céspedes, S., Zuñiga, A., Mendoza, A., Peña, W., Montero, K., & Chaves, M. (2020). Evaluation of the incorporation of Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC and Crotalaria spectabilis Roth, on the contribution and absorption of nutrients in rice cultivation (Oryza sativa). Repertorio Científico, 22(1), 29-37. https://doi.org/10.22458/rc.v22i1.2285

Doran, J. W., & Parkin, T. B. (1996). Quantitative indicators of soil quality: A minimum data set. En J. W. Doran & A. J. Jones (Eds.), Methods for assessing soil quality (pp. 25–38). Madison: Soil Science Society of America.

Garro, J. E. (2016). Soil and organic fertilizers (106 pp.). San José, Costa Rica: INTA.

Gatsios, A., Ntatsi, G., Celi, L., Said-Pullicino, D., Tampakaki, A., & Savvas, D. (2021). Legume-based mobile green manure can increase soil nitrogen availability and yield of organic greenhouse tomatoes. Plants, 10(11), 2419. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10112419

Hammed, T., Oloruntoba, E., & Ana, G. R. E. E. (2019). Enhancing growth and yield of crops with nutrient enriched organic fertilizer at wet and dry seasons in ensuring climate smart agriculture. International Journal of Recycling of Organic Waste in Agriculture, 8(1), 81-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40093-019-0274-6

Havlin, J. L., Tisdale, S. L., Nelson, W. L., & Beaton, J. D. (2013). Soil Fertility and Fertilizers: An Introduction to Nutrient Management (516 pp.). New Jersey: Pearson.

Kaniszewski, S., Babik, I., & Babik, J. (2019). New pelleted plant-based fertilizers for sustainable onion production. Universal Journal of Agricultural Research, 7(6), 210-220. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujar.2019.070603

Klassen, W., Codallo, M., Zasada, I., & Abdul, A. (2006). Characterization of velvetbean (Mucuna pruriens) lines for cover crop use. Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society, 119, 258-262.

Liu, Z., Howe, J., Wang, X., Liang, X., & Runge, T. (2019). Use of dry dairy manure pellets as nutrient source for tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L. var. cerasiforme) growth in soilless media. Sustainability, 11(3), 811. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030811

Martinez, H. E. P., de Andrade, S. A. L., Santos, R. H. S., Baptistella, J. L. C., & Mazzafera, P. (2024). Agronomic practices toward coffee sustainability: A review. Scientia Agricola, 81, 2022-2077. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-992X-2022-0277

Martínez-Alfaro, A., & Zuñiga-Orozco, A. (2024). Pelletized Mucuna pruriens (L) DC. and Trichoderma harzianum Rifai applied on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) as an amendment and biocontrol agent. Agronomía Mesoamericana, 35, 55389. https://doi.org/10.15517/am.2024.55389

Matos, E. S., Mendonça, E. S., Cardoso, I. M., Lima, P. C., & Freese, D. (2011). Decomposition and nutrient release of leguminous plants in coffee agroforestry systems. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, 35, 141-149. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-06832011000100013

Melendez, G., & Molina, E. (2002). Foliar analysis interpretation table in coffee (52 pp.). San José, Costa Rica: CIA-UCR.

Mendez, J. C., & Bertsch, F. (2012). Guide to the interpretation of soil fertility in Costa Rica (78 pp.). San José, Costa Rica: CIA-UCR.

Niguse, G., Iticha, B., Kebede, G., & Chimdi, A. (2022). Contribution of coffee plants to carbon sequestration in agroforestry systems of southwestern Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Science, 160, 440-447. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859622000624

Organo, N. D., Granada, S. M. J. M., Pineda, H. G. S., Sandro, J. M., Nguyen, V. H., & Gummert, M. (2022). Assessing the potential of a Trichoderma-based compost activator to hasten the decomposition of incorporated rice straw. Scientific Reports, 12, 448. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03828-1

Paolini, J. E. (2018). Actividad microbiológica y biomasa microbiana en suelos cafetaleros de los Andes venezolanos. Terra Latinoamericana, 36(1), 13-22. https://doi.org/10.28940/terra.v36i1.257

Pardo-Plaza, Y. J., Paolini-Gómez, J. E., & Cantero-Guevara, M. E. (2019). Biomasa microbiana y respiración basal del suelo bajo sistemas agroforestales con cultivos de café. Revista U.D.C.A Acta Científica, 22(1), e1144. https://doi.org/10.31910/rudca.v22.n1.2019.1144

Ravi, C., Hadapad, B., Shetty, R., Shrivaprasad, M., Bindu, H., & Prasad, M. (2018). Evaluation of velvet bean (Mucuna pruriens L.) genotypes for growth, yield, L-dopa content and soil nitrogen fixation in rubber plantation under hill zone of Karnataka. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 7(3S), 26-29.

Rojas, M., Rodríguez, J., Alcalá, J., Díaz, P., & Carballo, E. (2020). Ensayo en invernadero de abonos verdes sobre las propiedades del suelo, producción de acelga e implicaciones ambientales. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas, 11(4), 945-951. https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v11i4.2104

Rojas-Chacón, J. A., Echeverría-Beirute, F., Jiménez, J. P., & Gatica-Arias, A. (2024). Microorganismos de suelo y su relación con la calidad de la bebida de café: Una revisión. Agronomía Mesoamericana, 35(1), 57260. https://doi.org/10.15517/am.2024.57260

Wen, Y., Liu, W., Deng, W., He, X., & Yu, G. (2018). Impact of agricultural fertilization practices on organo-mineral associations in four long-term field experiments: Implications for soil C sequestration. Science of the Total Environment, 651, 591-600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.233

Xu, J., Si, L., Zhang, X., Cao, K., & Wang, J. (2023). Various green manure-fertilizer combinations affect the soil microbial community and function in immature red soil. Frontiers in Microbiology, 14, 1255056. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1255056